The Award-Winning Willie Cuesta Mystery Series, by John Lantigua

“A clear and forceful writer” — The New York Times

Remember my Face

“The rich and varied characters in this intriguingly twisty tale spring organically from the sandy soil of South Florida. This intelligent, timely novel is sure to win Lantigua new fans.” —Publishers Weekly

On Hallowed Ground

“This thoroughly entertaining crime novel flirts with a number of the genre’s central themes– kidnapping for ransom, drug dealing, betrayal, revenge, the silky seductiveness of a whole lot of money–filtering them through the special sensibility of Miami PI Willie Cuesta.” – Booklist Starred Review

“Lantigua knows the Caribbean and Miami the way Chandler knew Los Angeles.. A crackling good mystery, and I can’t wait for the next one!” —Paul Levine.

Burn Season

“Lantigua gives us a fresh, clever cast in a taut and authentic tropical thriller.” — Carl Hiaasen

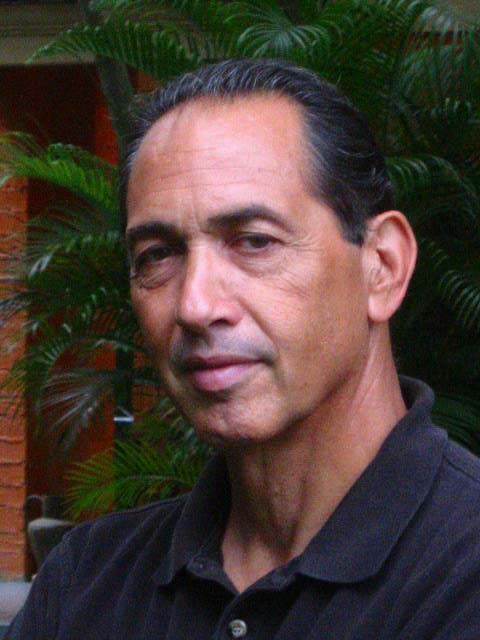

John Lantigua

Fiction

Lantigua’s latest Willie Cuesta novel, Remember my Face was a finalist for the 2021 Shamus Award for best original paperback. The series has been honored twice with the International Latino Book Award for Best Mystery, the first for The Lady from Buenos Aires in 2007 and the second for On Hallowed Ground in 2011. His debut novel, Heat Lightning, was nominated for an Edgar Award in 1987, and his Willie Cuesta short story, The Jungle, published in the anthology And the Dying is Easy, was a finalist for the Shamus award.

Journalism

Lantigua shared the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting and the Goldsmith Prize from Harvard’s Kennedy School for the Miami Herald’s reports on a tainted mayoral election.

He was also awarded the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Prize in 2004 and 2006 and the Hispanic Journalists Award for Investigative Reporting for his work on migrant laborers in the United States (2004) and on the dangerous misuse of pesticides in the fields of Florida (2006).

The National Association of Hispanic Journalists wrote:

“Accepting the award for print investigative news for a year long series about the dangers of pesticides to farm workers, John Lantigua thanked the undocumented workers who, he explained, “had to look into our eyes and say ‘Should we trust these people to tell them what we know?’” Lantigua was part of a team from the Palm Beach Post that also included Christine Evans and Christine Stapleton.”

John Lantigua’s private eye Willie Cuesta shows us Miami — via Latin America

Slaying South Florida Dragons: Veteran journalist and crime fiction author John Lantigua at work at his home in Miami Beach. — Photo by Edwina Lantigua

***

Few journalists understand Latin America and South Florida better than John Lantigua.

For four decades he chronicled everything from Miami’s civic corruption — for which he shared a 1999 Pulitzer Prize at the Miami Herald for reporting on election fraud — to Central America’s civil wars.

Today, Lantigua is a crime fiction writer, best known for his Willie Cuesta stories, which are set in South Florida but hearken back to Latin America. He presented the latest collection of stories featuring the fictional detective — called In the War Zone of the Heart — at Books and Books in Coral Gables.

One of the big messages Lantigua’s engaging Willie Cuesta tales convey is that when Latin Americans come to South Florida they often come fleeing political oppression and violence. They arrive with hopes but also nightmares provoked by what they escaped, and their stories become part of the fabric and the narrative of the region—including its suspense stories. A good example: the book’s title story, “In the War Zone of the Heart,” which is rooted in the Nicaraguan civil war of the 1980s.

“We know that there were families in Nicaragua who were divided by that war — the most famous being the family of Violeta Chamorro,” Lantigua told me, referring to the woman who became President of Nicaragua in 1990, after the civil war.

“She had four children, two of whom were members of the Sandinista Party, and two of whom formed part of the opposition. So I imagined a family from the northern part of the country, where a lot of the war was fought. The matriarch is a lady with twin sons, one of whom sided with the Sandinistas, one of who joined the Contra rebels.

“They also had a conflict in that they were both in love with the same woman. The brother who fought with the Contras ends up leaving Nicaragua, coming to the U.S. and bringing the woman with him.

“And this eventually leads the Sandinista brother to decide he can’t live with this — and he’s coming to South Florida, specifically the Sweetwater area, home to Miami’s large Nicaraguan community, and he’s going to hunt down his brother and get rid of him.”

Enter Cuban-American gumshoe Willie Cuesta, a former Miami cop, who gets hired to stop the deadly sibling rivalry. (Spoiler alert: he gets a little help from la madre, just as Nicaragua got it from Chamorro.)

Despite his keen eye for quintessentially Miami situations like that, Lantigua is not a Miami native: he was born in New York to a Puerto Rican mother and a Cuban father. But he knew at age seven he would eventually change locales.

“In 1955, my father put my mother and me in a car, and we drove to Key West to take the ferry to visit Cuba,” Lantigua recalls.

“And I’d never seen water that looked like that — Key West water — and something in my little seven-year-old brain told me: I want to live with that.”

So after covering the Central American conflicts, Lantigua did make his way to South Florida as a reporter for the Miami Herald. He not only got to know the city’s streets and barrios fairly deeply — his time in Latin America made him realize that you can’t really understand Miami and its people if you don’t also understand what they or their families went through back in places like Central America and Cuba and Haiti.

“Especially what they were running from,” Lantigua stresses. “A lot of people came here, and still come here, running for their lives.

“I mean, we know the story of the Cuban diaspora, but that’s true of many other nationalities — the Guatemalans, the Haitians, the Argentines, the Chileans. Running from both the oppression of communism and the oppression and violence of anti-commuism.”

Lantigua decided a Cuban detective was the best exponent for telling the police-blotter stories of both the angels and demons who get chased here. Years before he’d read an article about iconic private-eye author Dashiell Hammett, famous for The Maltese Falcon and his detective hero, Sam Spade.

“Hammett made Spade a sort of knight errant, like a knight of the Round Table, who is to go out and slay dragons, but in a 20th-century ambience,” Lantigua says.

“So suddenly the idea of quests came into my head, because when they knights went out to slay dragons they called it a quest. And then just as suddenly the relatively common Spanish surname Cuesta popped into my head, and moments later I heard the name Willie Cuesta.”

Lantigua points out that unlike himself, Willie Cuesta is “totally Cuban.”

“His mother is from the countryside, and she runs a botánica, a shop for herbal and religious remedies, in Little Havana. And sometimes Willie goes to her for advice about how to solve a crime.”

There are of course stories about Cubans in In the War Zone of the Heart. One about a wealthy Cuban exile woman who falls in love with a recently arrived Cuban man who claims to have been a longtime political prisoner on the island. Another about Cuban exiles and the properties many of them had stolen from them by the Cuban Revolution.

“To understand Miami you have to understand what people are running from in Latin America — and so many come here running for their lives.” — John Lantigua

In the latter, “The Man from Scotland Yard Dances Salsa,” Lantigua presents an older Cuban exile named Papi Planas — an engineer, he says, based on a real person he knew in Miami — who had escaped the revolution with reams of information about those properties from all over the island, and who sells the data to families who someday hope to reclaim them.

In one passage of the story, as Cuesta meets with Papi for some information that may lead him to a kidnapping ring — but also for an update on a property that belonged to Cuesta’s own family — Lantigua conveys much about the Cuban exile experience and its effects in a way that casts Miami’s Cuban community in a more complicated light:

He pointed at one of the filing cabinets. ‘Well, the deed is still there.

Someday maybe I can get you or other relatives restitution for what

was lost.’

Willie thanked him but didn’t really think the Cuban government

was going to be recompensing the Cuesta family any time soon.

Down deep, Papi suspected that too. After all these years he knew

that what he was really selling weren’t documents that might

someday be worth real money. What he was peddling were ties to

the past — which were so important to exile Cubans — and some

wistful, unrealistic dreams about the future. What those file cabinets

and computers contained were fantasies.”

Death squad

That’s a striking feature of Lantigua’s Willie Cuesta mystery stories: they move briskly, like any good cop reporting, but they still contain a rich store of information about Miami and South Florida.

That’s especially true of Little Haiti in the story “In the Time of Voodoo,” about a member of the Tonton Macoute — the monstrous death squad of Haiti’s Duvalier dictatorship — who finds his way to Miami and is discovered here by the expat daughter of one of his victims.

Knowing he’s been discovered — and knowing he’d be sent back to Haiti if U.S. officials find out he’s here — the man begins stalking the woman. Again, Willie Cuesta has to stop him from wreaking in Little Haiti the sort of terror he was responsible for in Haiti.

Lantigua was also a reporter for the Palm Beach Post — and his book’s first story, “The Jungle,” shows his familiarity with both the Guatemalan migrant worker community of that part of South Florida, and the immigration community.

“The Jungle” also resonates more at this moment, as Florida enacts a new law targeting undocumented immigrants. Another one of the regular heroes of his stories is a tough, smart Miami immigration attorney, Alice Arden, who often throws work the private eye’s way.

“I covered immigration for twelve-and-a-half years for the Post,” Lantigua recalls, “and one of my assignments was to get smuggled [like an undocumented migrant] across the Arizona desert.

“I have a fairly intimate knowledge of what it’s taken for some people to get here — and how desperate you have to be under those circumstances to get here. And it makes me not just more sympathetic to the Guatemalans, but to anybody, including people who put themselves on rafts from Cuba, or anyone coming through the Darien Gap in Panama.

“And making those lives more difficult I don’t think is in the interest of anyone … except maybe some politicians.”

– On Hallowed Ground –

“This thoroughly entertaining crime novel flirts with a number of the genre’s central themes– kidnapping for ransom, drug dealing, betrayal, revenge, the silky seductiveness of a whole lot of money–filtering them through the special sensibility of Miami PI Willie Cuesta.”